Very British China problems

London's awkward relationship with Beijing, laughing Xi, China launches another aircraft carrier, recommended articles and podcasts etc.

This week’s most important China news and best writing in English on China.

This week’s focus

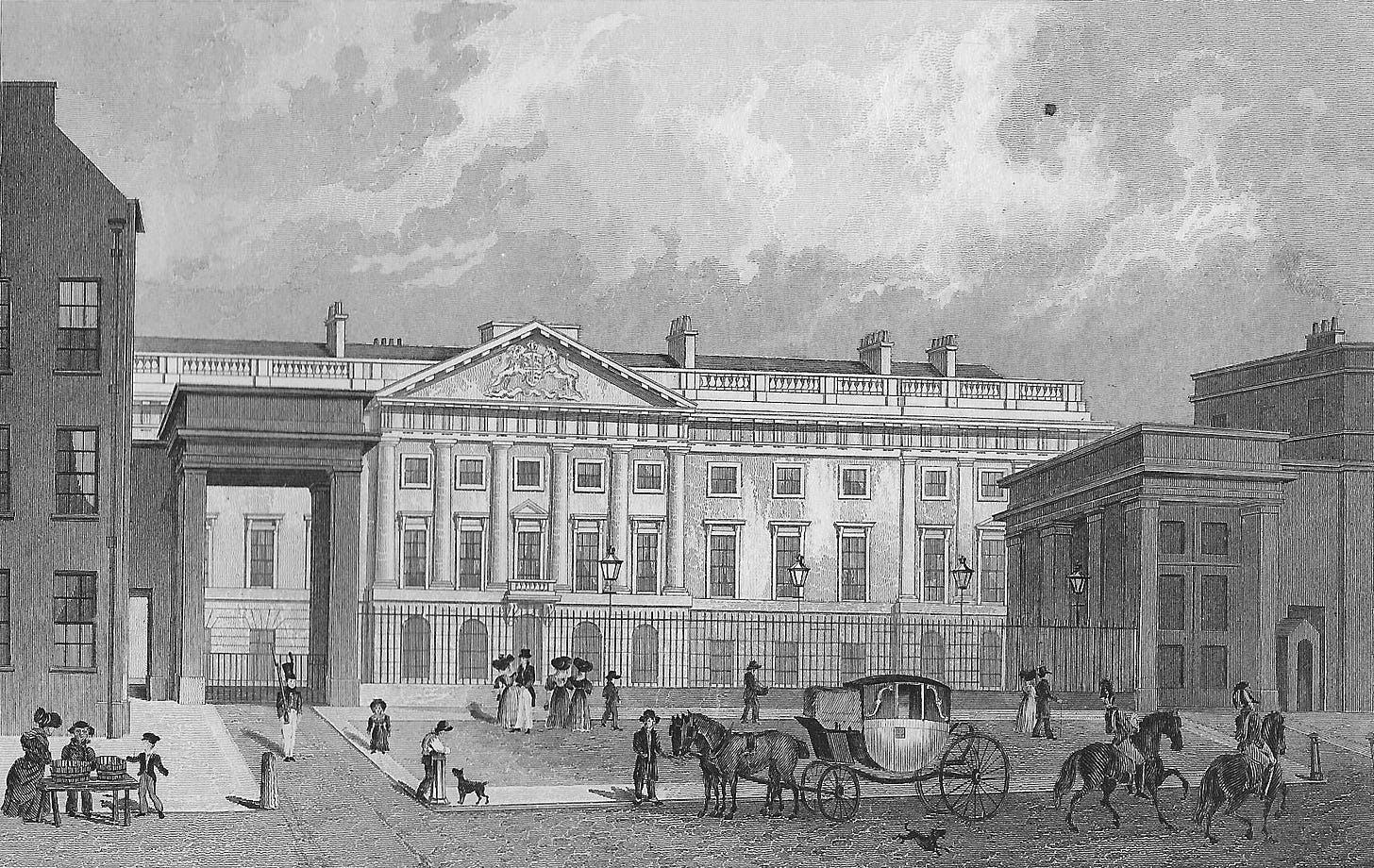

A season of unease over China in the U.K.

China-U.S. relations have been temporarily stabilized by the meeting between Xi Jinping and Donald Trump in South Korea on October 30. But in the United Kingdom, nobody seems to quite know how to approach Beijing.

The “golden era” of China-U.K. relations promised in 2015 by then prime minister David Cameron never worked out. The following five occupants of 10 Downing Street, including current prime minister Keir Starmer, have all dithered between welcoming Chinese money and fearing its influence, its espionage, and its manufacturing dominance.

In the last few weeks, three issues have clearly demonstrated the British government’s lack of a vision for relations with China:

The gigantic n…